Collection: Vytautas Kasiulis

The works of the world-renowned Lithuanian artist Vytautas Kasiulis (1918–1995) now adorn the modern art museums of Paris and New York, as well as art galleries in France, the USA, Canada, Great Britain, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, Argentina, Australia, and other countries. Art critics justly considered Vytautas Kasiulis one of the most interesting painters of the second half of the 20th century Paris School. Kasiulis arrived in the European art capital as a mature artist, having studied and taught at the Kaunas Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts (later the Art School) and the Freiburg School of Art and Crafts. By then, he had already won awards in various competitions and held several solo exhibitions that received favorable reviews. In 1948, Kasiulis began a new phase of artistic recognition in Paris. As a creator with an extremely receptive artistic nature, he radically changed his painting style and artistic character upon arriving in his dream city, integrating into the Parisian art community as an equal with his unique and original style. In 1960, the artist acquired his first private art gallery, where he exhibited works by famous representatives of the Paris School, later exchanging it for the larger and more respectable Galerie Royal in central Paris. Thanks largely to the energetic efforts of his wife Bronė Kasiulienė, the gallery maintained active exhibition and commercial activities until 1990.

In Paris, Vytautas Kasiulis revealed himself as a versatile artist, excelling in painting, graphics, and book illustration. His mature period is characterized by expression, refined color, decorativeness, and an ironic perspective. In Kasiulis's works, scenes of ordinary life transform into a strange spectacle balancing between reality and fantasy. Many art critics who wrote about his work compared him to Raoul Dufy, Georges Rouault, Marc Chagall, and other famous painters of the Paris School, while emphasizing his individuality and authentic talent.

Vytautas Kasiulis: "Enfant du siècle"

Ramūnas Čičelis

www.kamane.lt, 2017-10-06

There are artists shaped by the dominant discourse of their time—the sum of written, spoken, and visual texts they do not fully know but which significantly influence their thinking, imagination, and works. Until the mid-20th century, Western Europe and the United States experienced a period of modernity with a particular focus on place. Whether a philosopher, writer, or painter, their essential creative factor and condition was their place of residence—homestead, city, street, etc. With the post-World War II period of decentering the individual, place lost its former significance, becoming merely abstract, and later virtual, space. Time, whose flow still evokes a passion for living, learning, and creating, then took on the essential role.

Lithuanian émigré artist Vytautas Kasiulis (1918–1995), who learned the basics of art in Kaunas before the war, later moved through Germany to France, where he spent most of his life and is buried. This artist is a typical creator of the era of time importance, as his works reflect all the collective, creative consciousness shifts and movements of the mid-to-late 20th century.

Kasiulis began as a realist painter, a starting point common to many great figures of global modernist art, such as Pablo Picasso, who also began his creative biography as a realist. For the contemporary viewer living in an often intangible reality, Kasiulis's early works might be interesting as positively old-fashioned; they return the modern art viewer to what is still undeniably real and to the basis of individual philosophy—the presence of the object. The object, as something that has disappeared but is captured on canvas, can still serve as the foundation and reference point for personal philosophy for today's art consumer. In his early works, Kasiulis takes a dangerous step, surrendering to objectivity to the extent that the painting becomes a household artifact. Yet even in this case, his works convey that art, unlike before the 20th century and unlike now, when its understanding and interpretation often require special competencies, can be accessible even to those who are not professional art critics and have no connection to the humanities.

Another feature of Kasiulis's works again prompts questioning their artistic value, nearing the dangerous boundary of kitsch. The aim for the painting to be decorative and harmonize with its environment indicates the artist viewed his works not only with an aesthetic eye. Kasiulis did not shun a utilitarian approach to art—paintings were meant not only to be admired but also to decorate.

Painting almost daily, Kasiulis inevitably had to repeat the same themes and plots. Nevertheless, a closer look at several works on the same theme reveals that both his entire creative biography and several paintings with the same motifs are given the status of a literary work—recurring themes should be seen not as a lack of originality but as a realized opportunity to creatively continue his earlier ideas, developing them like a novel plot.

Understandably, Kasiulis's most interesting period is his modernist phase, lasting until his death. Here, the artist offers the contemporary viewer a chance to relax: amidst the fragmentariness, inconsistency, and chaos of our lives, people need something to make them step back and look at problems from a distance. Kasiulis's modernist works provide just such an opportunity. With their mosaic-like nature, seemingly chaotic color, often dominated by light tones, they offer one of the few chances not to participate in either the painting before one's eyes or the spectacle of life as a whole. It is an opportunity to temporarily withdraw from what French philosophers call the "society of the spectacle." The paradox is that by creating this visual spectacle, Kasiulis allows the viewer, through aesthetic distance requiring psychological and physical space, to become a sort of calm trickster—viewing the world's noise and personal questions and inextricable Gordian knots with some irony and reordering life's chaos as they wish.

Despite potential criticisms of Kasiulis for catering to public taste and adapting to contemporary trends, it must be acknowledged that he had an individual style expressing a very unique imagination shaped by what is colloquially called life—experiences that no one else has. This trait is unique to Kasiulis but also applies to many painting masters, as there is no one whose imagination-forming experience is absolutely identical. Kasiulis viewed culture as Yuri Lotman defined it—as text, creating and emphasizing practices through his works that transform a person into an individual touched by rich imagination and culture, rather than a being exhausted by sensory experiences. This aim marks the beginnings of postmodern thinking and creativity, which Kasiulis clearly felt and expressed towards the end of his life.

An "enfant du siècle," a child of the century, Kasiulis emerged as a creative personality of exceptional sensitivity to the environment and humanity, clearly understanding the main contemporary human issues: uncertainty about the future, insecurity, and the decentering of the individual as a complication. Examining Kasiulis's entire painting oeuvre reveals that, in his case, the dimension of time, not inherent to painting by nature, is crucial. This is discussed in art criticism when a long and diverse creative path is discovered.

-

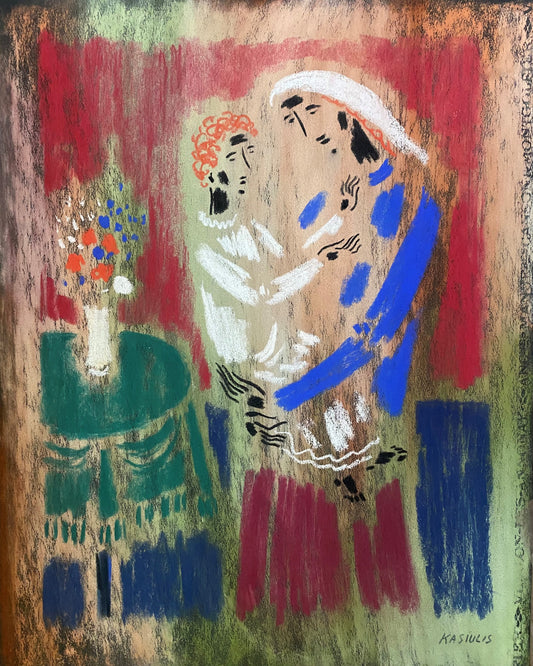

Vytautas Kasiulis | Scene | Pastel on paper, 50x65 (56x71)

Regular price €3.000,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Painter with model | Oil on canvas, 73x93 (86x106)

Regular price €11.500,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Musicians | Oil on canvas, 92x73 (115x96)

Regular price €9.700,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Still life with pears | Oil on canvas, 64x80 (78x93)

Regular price €6.600,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

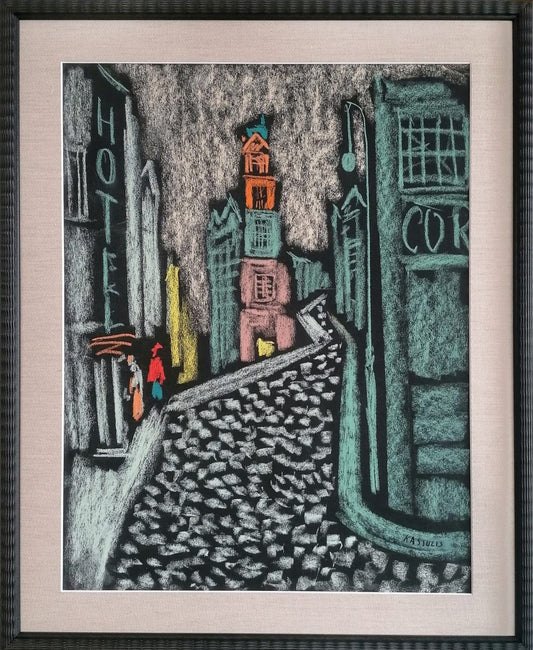

Vytautas Kasiulis | Paris motif | Pastel on paper, 65x50 (78x63.5)

Regular price €2.500,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

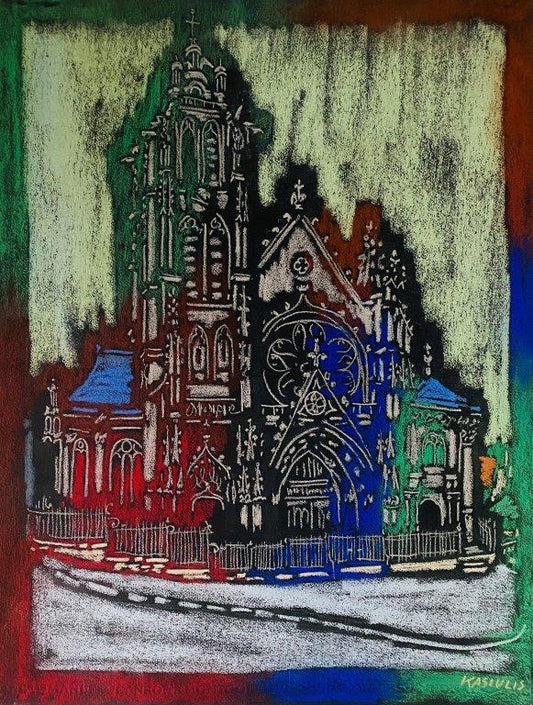

Vytautas Kasiulis | Saint Maclou Cathedral in Pontoise | Pastel, paper, 65x50 (84x69)

Regular price €2.400,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

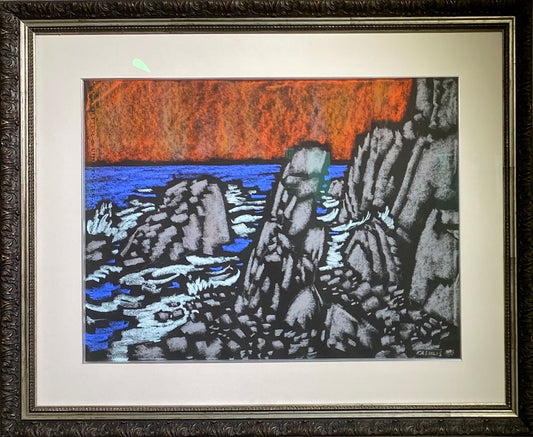

Vytautas Kasiulis | Seashore | Pastel, paper, 49x64 (73x89)

Regular price €2.400,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Zuzana | Lithograph, 53/100, 32x47 (56x71)

Regular price €580,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

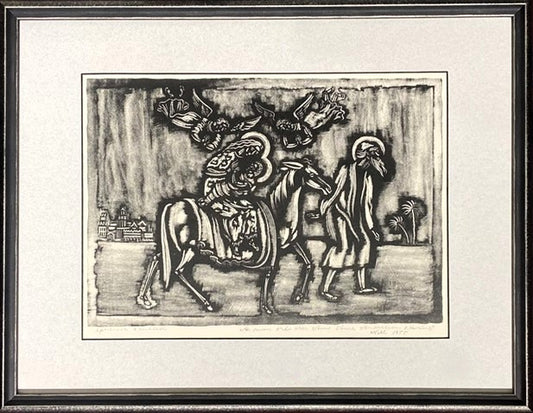

Vytautas Kasiulis | Flight into Egypt | Lithograph, 21x30 (34.5x44.5)

Regular price €350,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Circus artist on a bicycle, 20th c., 6th-7th dec. | Gouache, paper, 37x50 (51x64)

Regular price €2.200,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Seaside town street | Lithograph, 17x22 (26x32)

Regular price €300,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas KASIULIS | Landscape | Pastel, paper, 50x65

Regular price €2.400,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Relaxing by the lake | Oil on canvas, 73x92 (88x108)

Regular price €12.000,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Hipster with pitchfork | Pastel on paper, 65x50 (71x56)

Regular price €2.400,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Mother with Child, 5-6 dec. of the 20th c. | Pastel, paper, 57x46 (84x69)

Regular price €2.600,00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Vytautas Kasiulis | Woman reading, 1950 | Canvas, oil, 46x61

Regular price €0,00Regular priceUnit price / per